Familial strife has been around the days of Adam and Eve. But today, it increasingly seems to manifest itself in family estrangement. Catholic families aren’t immune to the heartbreaking phenomenon.

Deacon Aaron Petersen experienced it firsthand.

Deacon Petersen recounted to OSV News how, as a then-18-year-old, he was sick of being the go-between for his divorced parents. One day, he walked into his father’s office and demanded the behavior stop. Angered by his son’s disrespectful tone, Petersen’s father began to shout back. The heated exchange ended with the young Petersen walking out of the room, his father’s voice still echoing in his ears. “Get the hell out of my office,” his dad had said. “Get the hell out of my life.”

The sting of his father’s words intensified the sadness and abandonment he felt over his parents’ divorce. In his heart, Petersen knew that his father truly didn’t want to cut ties. But it didn’t matter. He didn’t want his father in his life anymore. Years began to pass this way between them, one after another.

About one in four Americans are alienated from an immediate family member, according to a 2022 YouGov survey.

Media outlets such as The New Yorker, The Guardian and Slate recently have published pieces about the growing trend of adult children severing ties with their parents. Each adult child has his or her own reasons for the separation, ranging from abuse and addiction to fundamental disagreements over religion and politics.

But every estrangement, whether motivated by ideological differences, a fear for one’s safety or something else entirely, is a tragedy that reveals a loss of the original plan God had for humanity, said Allison Ricciardi, a licensed mental health counselor and the founder of catholictherapists.com.

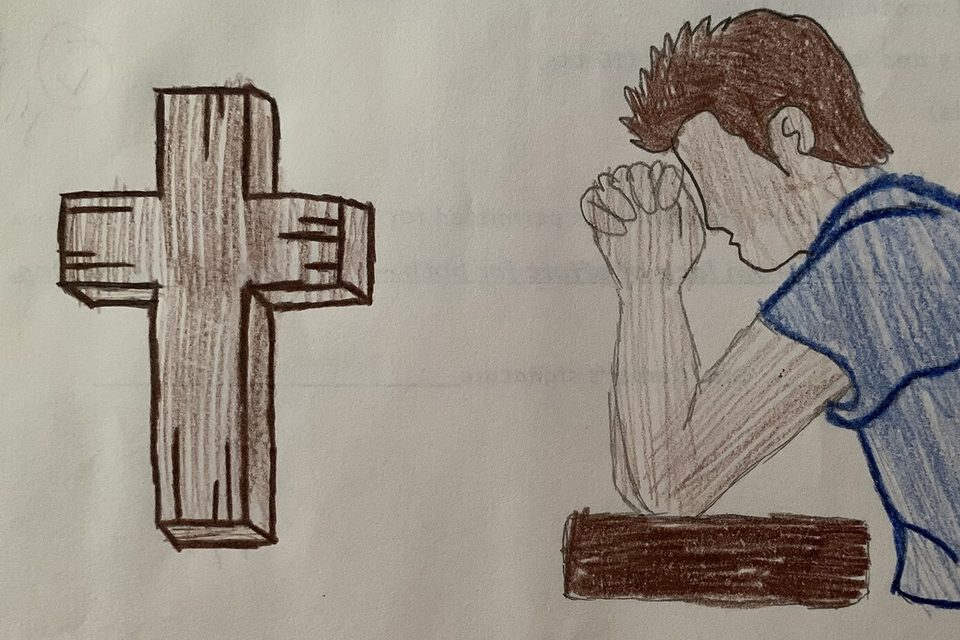

“I’m seeing it everywhere – we’re seeing the division, and division doesn’t come from God,” she told OSV News. “As Christians, hope springs eternal. We should always be praying for healing and reconciliation.”

Tyler, a Catholic husband and father, didn’t know he was part of a trend when he decided to put some distance between himself and his parents.

“I was a little bit surprised,” said Tyler, who preferred to use a pseudonym due to the sensitive nature of the topic. “If you read about it online or on Reddit, people use the abbreviation nc (for no contact) – it’s a recognizable phenomenon so much that people have acronyms for it.”

The estrangement between Tyler and his parents began when his parents moved in with him after his father lost his job. Certain bad behaviors, especially from his mother, soon became more apparent and disturbing.

“My mother is basically narcissistic – she has this belief that she’s smart and special in ways that most other people don’t understand,” he said. “Her personality has always kept her from making close friendships with other people. In lieu of that, she’s kind of had this weird dependence upon all of her children as the people to whom she doesn’t have to make friends with, the people she can just be toxic to and who just deal with it.”

When his parents moved out, Tyler told them he needed a little emotional space. But after he got married and had his first child, he realized he wanted a more long-term separation.

“What kind of people do I want around (my kid)?” he said. “It’s not just the narcissism – I could never take them over to my parents’ place because it’s literally just filthy; it’s just not a safe place.”

However, Tyler does maintain some contact with his father.

“I still call him on Father’s Day and things like that,” said Tyler. “He always drops the line like, ‘Hey whenever you’re ready, we’re happy to come visit or do something.’ But he doesn’t push it, and I appreciate that.”

Tyler and his family live close to his wife’s parents, and he’s grateful his children can have a relationship with at least one set of grandparents. He himself never knew his maternal grandfather, as his mother and grandfather had a bad relationship. Sometimes Tyler wonders where this generational pattern of estrangement will end.

“Ideally, my kids would have a relationship with my parents and I would have a better relationship with my parents,” he said. “(But) I don’t want to prioritize (breaking the pattern) at the expense of my kids’ general well-being.”

Veronica Picone went from seeing her grandchildren on a nearly daily basis to having the Christmas gifts she bought for them returned to her unopened. Five years ago, Picone’s daughter sent her a text message ending their relationship, and by extension, cutting her off from her grandchildren. Picone’s younger daughter, who she believes felt caught in the middle, eventually cut off contact, too.

“It was a complete surprise to me,” she told OSV News. “Although we’ve had our rough times when she was young, for the last 20-something years, we’ve been very close.”

She believes the seeds of division first were sown when she and her daughters’ father separated. “I was a single mother and I worked three jobs,” she said. “I was a devoted mother, but I made a lot of mistakes.”

In her grief over the separation, Picone turned to the Church. When she learned her parish didn’t have a support group for estranged parents, her parish priest encouraged her to start one. The support group is called More Than Ever, a line taken from a prayer in the Mass of reconciliation: “When we were lost and could not find the way to you, you loved us more than ever.”

The group, based at St. Mary’s Church in Pompton Lakes, New Jersey, now has 16 members, Picone said. They talk about grief, surrender, forgiveness, introspection and self-care. They bond over the unexpected wounds, such as the shame and awkwardness that comes from interacting with other parents and grandparents.

Picone still doesn’t understand why God has allowed this estrangement, or what good can possibly come from it. But her faith still has given her great comfort.

“Through the tender reception and care that my parish has offered, and being able to pray together and to share together as a group – that has begun to plant the seeds of hope,” she said. “I don’t mean this in a dangerous way, but there were many mornings when I just didn’t want to wake up. I just didn’t want to face the devastating rupture this left in our family. Today, it hurts, but this is my life. God must want me for something.”

In her therapy work, Ricciardi sees many clients struggle with knowing when to limit contact, or how to interact with difficult loved ones when they do spend time together. Therapy can often help people learn coping skills and to set boundaries, she said.

“Let’s say every holiday gathering, mom gets really drunk and she humiliates me in front of everybody. Well, that’s kind of a no-brainer – why would you go?” said Ricciardi. But a parent’s bad decisions doesn’t always necessitate a total separation, she added.

Ricciardi advises parents to treat their adult children as adults, to assume their child’s good intentions and to allow them to express themselves without showing judgement. She encourages adult children to acknowledge the good things their parents have given them, but to feel OK with saying no in certain situations. During gatherings where there’s a possibility of conflict: have games or other activities ready and steer the conversion toward areas of common ground. Limit alcohol consumption, and as a last resort, have an exit strategy.

Above all, try not to let differences in opinion drive a wedge, said Ricciardi. “We’re becoming more and more isolated, siloed in this kind of groupthink,” she said. “I think the trend we’re seeing is (people saying), ‘I disagree with your values, I disagree with your politics, therefore I can have nothing to do with you because I have judged you to be irredeemable.’”

Tyler hopes that others like him try not to see the estrangement as a permanent measure.

“Treat it the way you might make any other decision about where to work or live. Be ready and willing to honestly evaluate it,” he said. Don’t stew, either, he added. “If you need to move away from the heat, that’s fine – but don’t live in anger or resentment,” he said.

Picone encourages parents with estranged children not to base their self-worth on what their children think of them. “(I hope parents) remember that they are children of God, that Christ loves them,” she said. “That no matter what mistakes they made, even though this feels like punishment, this is really just a consequence of things that happened long ago.”

Deacon Petersen told OSV News how one day, as a married man with children of his own – years after having cut off his father – his son asked him a question he didn’t know how to answer: “Why don’t we hang out with Grandpa Petersen?” As he had discerned a call to the permanent diaconate with the Diocese of Lansing, Michigan, the future deacon began to reflect more on the estrangement.

He decided to talk the matter over with his pastor, explaining that he was still upset with his dad for leaving the family.

“How long have you abandoned your dad?” the priest responded. The powerful question helped Petersen realize that the hardness he felt in his heart toward his father was impacting all his relationships.

“What you don’t transform you transfer,” Deacon Petersen said, reflecting on those events.

Deacon Petersen then shared what happened when he decided at last to bring his family to see his father and stepmother. On the long drive, he mulled over how to tell his dad that he forgave him. But by the end of the journey, he realized he was the one who needed forgiveness. His father readily offered it.

“It was truly a prodigal son moment. When I drove up, he was standing in the window. He came out and gave me a hug and a kiss, and then we had a feast,” Deacon Petersen said. “I don’t think any human heart is perfectly without hardness, but it took 90 percent of that hardness away.”