When word spread on Aug. 15, 1945 of Japan’s surrender, ending World War II, people flocked to the Cathedral of St. Matthew the Apostle in Washington, D.C., to offer prayers of thanksgiving that the deadliest war in human history was over. The fighting in World War II left more than 50 million people dead, including an estimated 15 million military personnel and 38 million civilians.

In Nagasaki, Japan, the Urakami Cathedral – which at that time was believed to be the largest Catholic church in East Asia – lay in ruins. The atomic bomb that the United States dropped on Nagasaki on Aug. 9, 1945 left a burning hellscape in that city, leveling buildings and killing more than 70,000 people, many instantly and others from the lingering effects of radiation. The bomb that exploded over the city detonated an estimated 500 meters from the Immaculate Conception Cathedral in Nagasaki, known as the Urakami Cathedral after the district of the city where it was built.

The Urakami Cathedral had been built brick by brick by Catholics and was a monument of faith to a Christian community that had endured centuries of persecution in Nagasaki, a city where saints were martyred and generations of “hidden Christians” kept the faith and passed it on, even when priests were forbidden to serve there.

The atomic bombing of Nagasaki killed about 8,500 of the cathedral’s 12,000 parishioners. After the bombing, a prominent Catholic there – Dr. Takashi Nagai, a physician and radiologist – encouraged people to keep the faith. While suffering from a serious head injury in the aftermath of the bombing, he cared for survivors and witnessed the bomb’s horrific effects on the dead and on the living. He returned home to find his house destroyed and his beloved wife, Midori Moriyama, dead. Amid her charred remains, he found a melted rosary that she prayed with. Dr. Nagai became a world famous advocate for peace and forgiveness after the war before dying of leukemia six years later. Causes for canonization for Dr. Nagai and his wife are now underway.

Dr. Nagai encouraged fellow Catholics to dig in the cathedral’s ruins for a bell that had called them to prayer from one of its two bell towers. While one bell had been found damaged and unusable, the volunteers unearthed the second bell and found it intact and relatively unscathed, and they rang it out on Christmas Eve in 1945, offering the city’s surviving Catholics an enduring sign of hope. Ichitaro Yamada, Dr. Nagai’s friend who led the volunteers in digging out and raising the bell, then rang the bell every day for decades. A new Urakami Cathedral was rebuilt and dedicated in 1959 on that site, and brick tiles were added to its exterior in 1980 so it could more closely resemble the original cathedral.

Now a scholar who has written about the moral implications of atomic weapons and who is writing a book on the historic legacy of faith of Nagasaki Catholics is leading the Nagasaki Bell Project, an effort to encourage U.S. Catholics to support the casting of a new bell for the Urakami Cathedral as a sign of solidarity and faith in time for the bell to ring out on Aug. 9, 2025, the 80th anniversary of the bombing.

James L. Nolan Jr., the Washington Gladden 1859 Professor of Sociology at Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts, was inspired to undertake the project while visiting Nagasaki in the spring of 2023 and doing research and interviews for a book he is writing on how Catholics in Nagasaki have experienced suffering through the centuries and despite that, their faith has endured and been marked by a spirit of hope.

“One of the parishioners at Urakami Cathedral at the end of my interview suggested that it would be wonderful if American Catholics gave a bell for the left tower of the Urakami Cathedral,” Nolan said. “Now the right tower has a bell in it, in fact it was a bell from the original cathedral… and that bell was then put into the right tower when the cathedral was reconstructed after the war. And the left tower has remained empty all these years, and the bell from that tower was destroyed. And so what he was suggesting, is that wouldn’t it be wonderful if some American Catholics gave us that bell. And he said he would like to hear it ringing in his lifetime.”

Nolan said he thought that was a fantastic idea, and he has been working on that project since then. As of November, the Nagasaki Bell Project had raised just under $52,000 of the estimated $125,000 will cost to cast, ship and install the large bronze bell. A foundry in St. Louis is making the new bell, which will look much like the original.

The effort is being undertaken by the St. Kateri Institute, founded by faculty, alumni, students and friends of Williams College that promotes the Catholic intellectual tradition and is named for St. Kateri Tekakwitha, the “lily of the Mohawks” whom the institute notes “found nourishment and life in the beauty, truth and goodness of the Catholic faith.”

The original bell had been donated by French Catholics and featured St. Martin of Tours. The new bell’s design will include some of the Latin that was inscribed on the original bell, and since it will be a gift from American Catholics, it will include an image of St. Kateri, the first Native American to be recognized as a saint by the Catholic Church.

Describing the Latin inscription from the original bell that will be repeated on the new bell, Nolan said, "This is a rough English translation of the Latin, ‘I sing to God with a constant ringing in the place where so many Japanese martyrs with honor have praised and have by their example called their brethren and their descendants to the fellowship of the true faith and of heaven.’” He added, “That’s going to stay on the bell. And I love that. I love that. Isn’t that beautiful? The ringing of the bell itself, as described in the Latin, is a calling to mind of the years of faithful suffering and the martyrdom of the many Catholics who stayed true to the faith, and a calling to mind (of) their example. I think that’s fantastic, that’s beautiful.”

That witness of faith has inspired Nolan to write his latest book, and to undertake the Nagasaki Bell Project.

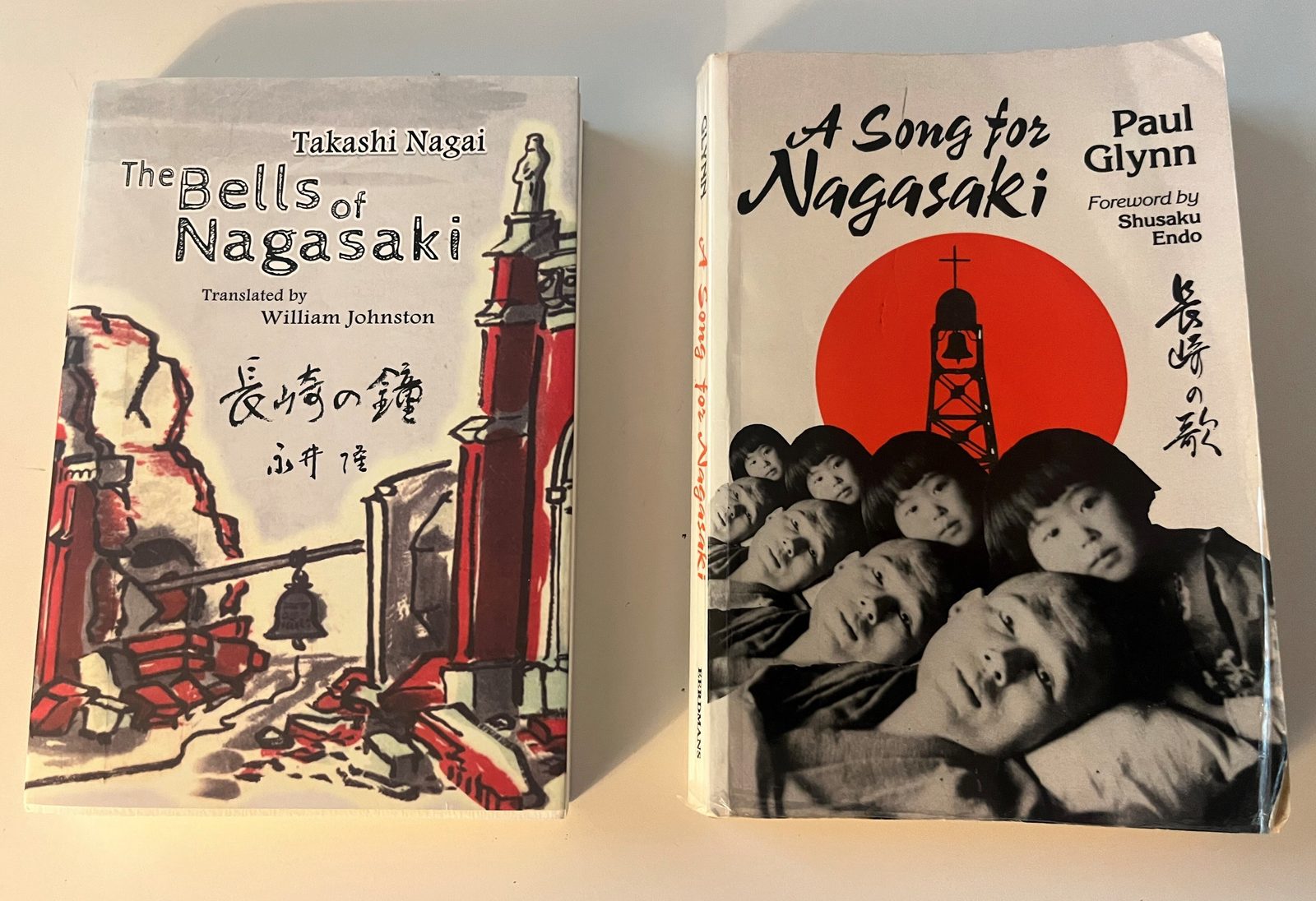

The Jesuit missionary St. Francis Xavier landed in Japan on Aug. 15, 1549 and first brought Catholicism to that country. In his book “A Song for Nagasaki,” Father Paul Glynn, a Marist priest, wrote how within a few decades, “great numbers of samurai and tens of thousands of lowly peasants and townspeople asked for baptism.” Japan’s ruler then banned Christianity, ordered all Japanese Christians to renounce their religion, and ordered foreign missionaries to leave.

In 1597, 26 Japanese Christians were arrested and forced to march barefoot for 30 days to Nagasaki, where they were hung on crosses on the Nishizaka Hill overlooking the city. Brother Paul Miki, a Jesuit, was among those Christians, and he told the crowd that he was Japanese and was only being killed because he taught the doctrine of Christ. “Ask Christ to help you to become happy. I obey Christ,” he said. Before soldiers pierced his chest and the chests of the other prisoners with lances, Brother Miki said, “I hope my blood will fall on my fellow men as fruitful rain.” St. Paul Miki and the other 25 martyrs of Japan were canonized in 1862.

A Franciscan Media website notes that when Catholic missionaries returned to Japan in the 1860s, they found that thousands of “hidden Christians” in Nagasaki had secretly preserved the faith for generations.

But between 1869 and 1873, more than 3,600 Christian villagers in Nagasaki were exiled by ruling authorities, and 650 of them died in exile during that persecution. After the exiled Christians returned to Nagasaki, the faithful there began building the Urakami Cathedral in 1895 after the ban on Christianity was lifted. The cathedral was completed in 1914, and it was reportedly the largest Christian church in the Asian-Pacific region until it was destroyed by the atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki in 1945.

Midori Moriyama’s ancestors had been leaders among the hidden Christians in Nagasaki for seven generations. Dr. Takashi Nagai lived at their family home during his medical school studies, and when he decided to convert to Catholicism, for his baptismal name, he chose “Paul” after St. Paul Miki. Before World War II, Dr. Nagai got to know the future St. Maximilian Kolbe, who started a Franciscan monastery in Nagasaki before later giving up his life for another prisoner at the Auschwitz death camp in Poland in 1941. Dr. Nagai married Midori, and they had two children who were sent to safety in the countryside after the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, on Aug. 6, 1945.

Professor Nolan said Dr. Takashi Nagai offered an inspiring witness of faith after the atomic bomb hit Nagasaki.

“His story is remarkable,” Nolan said. “…He (Dr. Nagai) was right near the epicenter and sustained injuries. And yet despite his injuries, despite of the fact that he had leukemia, and received more radiation from the bomb, he served his community. He sought to help people, and he sought to help rebuild the church (and) the community. He wrote, and he gave much of his proceeds from his books to helping to rebuild Nagasaki. It’s just an amazing story.”

Dr. Takashi Nagai wrote a book about the Nagasaki bombing and its aftermath, “The Bells of Nagasaki,” which he called “a human memoir” that he hoped would inspire people to work for peace and oppose war. In November 1945, he was invited to speak at a Requiem Mass for the victims of the atomic bomb there. He noted the history of faith of Nagasaki’s Christians, and he contended that the deaths of so many of them in the bombing ultimately could be seen as a sacrifice to God for peace.

In his talk at that Requiem Mass, Dr. Nagai said, “Our church of Urakami kept the faith during 400 years of persecution when religion was proscribed and the blood of martyrs flowed freely. During the war, this same church never ceased to pray day and night for a lasting peace. Was it not, then, the one unblemished lamb that had to be offered on the altar of God? Thanks to the sacrifice of this lamb, many millions who would otherwise have fallen victim to the ravages of war have been saved.”

Nolan noted that Dr. Nagai offered a Catholic perspective on suffering, emphasizing the need for forgiveness and peace and the need to rebuild, instead of responding with anger, bitterness and retribution. “That’s how he could understand the bombing as a kind of peace offering to end the war and to bring peace to the world,” Nolan said.

In the last chapter of “The Bells of Nagasaki,” Dr. Nagai issued a heartfelt plea for peace and against nuclear war, writing, “Men and women of the world, never again plan war! With this atomic bomb, war can only mean suicide for the human race. From the atomic waste, the people of Urakami confront the world and cry out: No more war! Let us follow the commandment of love and work together. The people of Urakami prostrate themselves before God and pray: Grant that Urakami may be the last atomic wilderness in the history of the world.”

The way that Dr. Nagai endured suffering with faith and grace offers an example to Catholics today, Nolan said. “You look at his life. Here is a person who lost everything. He lost his wife. He lost his health. He lost his community. He lost his job. He lost many of his friends, and he lost his church. In the midst of all of that, he remained joyful, hopeful and offered a narrative of peace and forgiveness. It’s remarkable.”

Nolan’s interest in Nagasaki’s Christians was spurred by trips to that city and to Hiroshima when he was writing “Atomic Doctors: Conscience and Complicity at the Dawn of the Nuclear Age.” After his father’s death, he received a box containing the personal papers of his grandfather, Dr. James F. Nolan, an ob-gyn radiologist who served as a doctor for the Manhattan Project, and was among of a group of doctors, scientists and military officials who went to Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the month after the bombings to assess the damage.

“At that time, people were still dying from radiation exposure and from injuries sustained from the bombing,” Professor Nolan said. “It was in following his (my grandfather’s) journey that I myself went to Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and in going to Nagasaki, I began to learn about the history of the hidden Christians, of the Catholics who lived in that area, and I learned that the bomb was basically dropped on the center of the Catholic community (there).”

Nolan said that in researching and writing his book “Atomic Doctors,” a pattern emerged about the doctors connected to the Manhattan Project. “Doctors offered warnings (about the dangers of atomic weapons). Doctors were ignored or dismissed, or the information they gave was misused or ignored. But then they were also complicit in the sense, there was nothing more they could do,” he said.

His grandfather didn’t want to talk about the war, but he did tell one family member about what he saw in those Japanese cities that had been hit by atomic bombs. “He finally said, ‘It was utter destruction, the likes of which you can’t even imagine.’”

Writing that book inspired Professor Nolan to write a book on the history of Catholics in Nagasaki. Noting how they kept the faith during times of persecution and passed it on from generation to generation for 250 years without priests, he said, “It’s a legacy of suffering but staying faithful, and also staying hopeful.”

If the Nagasaki Bell Project is successful, Professor Nolan hopes to be at Urakami Cathedral in August 2025, to mark the 80th anniversary of the atomic bombing of Nagasaki by hearing the new bell ring out there. “It will be incredibly meaningful. I want to join with the parishioner who asked me and said that he wants to hear that. I do, too.”

The ringing of that new bell in the Urakami Cathedral would continue a goal of Dr. Takashi Nagai, who in “The Bells of Nagasaki” wrote about what it meant when the unearthed bell from the cathedral’s ruins rang out once again: “I pray and strive for this bell of peace to continue ringing until the last day of the world.”

Related website links:

St. Kateri Institute

The Nagasaki Bell Project

https://stkateriinstitute.org/nagasaki-bell-project/

Related article:

New Mexico archbishop says Nobel Peace Prize for Japanese atomic bomb survivors ‘fitting’ amid global tensions